Majestic, not immortal 🦅

Bald eagles’ rebound is, perhaps, the greatest American wildlife success story. Now what?

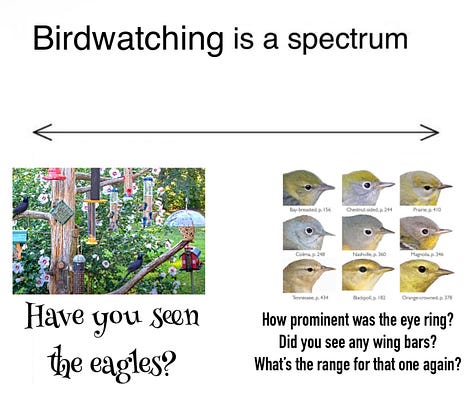

Non-birders’ fascination with bald eagles is something of a recurring joke in a few of the online birding spaces I frequent.

The idea is usually along the lines of a seasoned birder at a park being peppered by questions of “Have you seen the eagles?” by earnest strangers who spot their binoculars and assume they, too, are enthralled by the once-endangered birds of prey.

At the risk of allowing this meme out of containment, I want to offer one birder’s perspective on bald eagles:

I’m excited about seeing them, too!

Yes, please, tell me about the eagle (note the lowercase “e,” here) you saw last week on the way to your cousin’s house!

Yes, I’d like to hear about the eagles nesting near your favorite campsite!

You can always share your eagle stories with me – I’m interested!

(And while we’re chatting; no – a bald eagle is not a threat to kids or supervised pets. Eagles, by and large, prefer fish. They tend to avoid mammal meat, unless it’s from an animal that’s already shuffled off this mortal coil.)

Generally speaking, hardcore birders are focused on finding unusual, rare or tough-to-spot/ID birds – something that represents a bit of a challenge. Bald eagles, while not outrageously common, are easy to pick out and identify. These traits make them popular for non-birders and a bit of a non-event for intense birders. (Though, I’d argue, only the most jaded birders are immune to the sight of a majestically soaring eagle!)

What’s interesting about the eagle meme – and the entire reason for my risking the Streisand effect by bringing it up while simultaneously hoping to subdue it – is that just a few decades ago, it would’ve been outlandish to have a joke premised on the notion that a bald eagle is so run-of-the-mill as to warrant little more than a stifled yawn from any card-carrying Audubon club member.

As far as I’m concerned, every bald eagle is a miracle. We were so close, multiple times, to losing this species, how can you NOT feel a twinge of pride, excitement and wonder anytime you get a glimpse of one in the wild? Most birders I know IRL – even the staunch listers and rarity chasers – are excited when they see an eagle. Birders of a certain age, especially, remember when the skies were largely absent of the soaring predators. They do not take the species for granted.

A conservation success still in progress

In his 2023 book, “Ten Birds That Changed the World,” British nature writer and environmentalist Stephen Moss holds up the bald eagle as one of his titular transformative birds. Moss considers the bird’s history in human iconography and lore, its fierce reputation as an apex predator and its incredible recovery after nearly being wiped from the planet. Not gonna lie – some of the bald eagle chapter is pretty rough going, particularly the exploration of the hate groups and machines of war that have co-opted the eagle as a tool of propaganda and symbol of power/cruelty.

Less psychologically heavy/soul-crushing, but still ethically troubling, is the United States’ centuries’ long use of the bald eagle as a mascot while failing to protect it.

How have the American people, and their state and federal governments, meanwhile, looked after the actual bald eagle since it was first selected as the symbol of the fledgling United States of America? The simple answer would be ‘Not very well at all.’

By 1930, conservationists were warning that the bald eagle was in very real danger of going extinct … one eminent ornithologist (stated) that ‘In a few years, the American bald eagle will be seen only on coins and coat of arms of the United States unless drastic action is taken to save these birds from extinction.

Hunting and deforestation were among the top reasons for the eagles’ decline in the early 20th century. This loss was accelerated in the 1940s beginning with the widespread use of the powerful insecticide DDT. Legendary biologist/conservationist (and personal hero) Rachel Carson helped bring the threats of DDT to public consciousness in her seminal 1962 book, “Silent Spring.” On the topic of eagles, specifically, Carson noted:

On Mount Johnson Island as well as Florida, then, the same situation prevails – there is some occupancy of nests by adults, some production of eggs, but few or no young birds. In seeking an explanation, only one appears to fit all the facts. This is that the reproductive capacity of the birds has been lowered by some environmental agent that there are now almost no annual additions of young to maintain the race.

For those unfamiliar, DDT – which was used to suppress mosquito and other insect populations – washed into waterways, where it was absorbed by aquatic plants and fish. Eagles consumed the DDT-contaminated fish, with cumulative effects. The chemical interfered with birds’ ability to produce eggshells strong enough to endure incubation, meaning many nests failed to yield offspring.

Eagles and other birds at the top of the food chain weren’t the only ones affected by DDT; Michigan’s own state bird, the American robin, was severely harmed, too. (It’s also worth considering that the widespread, take-no-prisoners use of any insecticide is always going to harm birds in some way, shape or form, as most land species feed on insects.)

Thanks to the tireless efforts of folks like Carson and countless others – including the private citizens who petitioned the US government for policy change – we are fortunate enough today to be in a position to even remotely contemplate a bald eagle as being mundane.

Personally, I am grateful for every single bald eagle I’ve seen. No matter how many times I’ve clocked one – whether it’s soaring elegantly in the sky, or scavenging amongst the garbage at the local dump – it’s a rush of excitement.

The eagles have landed

Remember how I said I’ll always listen to others’ eagle stories? Well, I’ve got a few of my own, and now you’re going to hear about them:

There’s a beloved nesting pair at one of my favorite nearby hotspots. The local birding community anxiously tracks their annual successes and failures as you would monitor updates from a favorite family member. When the pair’s massive nest – did you know the bald eagle constructs the largest arboreal nest of any bird in the world? [Moss, 2023] – was destroyed a few years ago in a windstorm, we were collectively shattered. Fingers crossed for this breeding cycle. As I write this, I’ve just returned from watching the nesting adults who are rumored this spring to have two eaglets. While the babies weren’t visible to me on this visit, I’m hopeful to see them on my next outing so I can capture some terribly pixelated iPhone snaps.

Hiking with my mother-in-law around Wakeley Lake in Grayling, Mich., we startled an until-then-unseen bald eagle perched in a nearby tree, which was located down a slope, but roughly at eye level. While we felt terribly for spooking the eagle, I can attest that his sudden motion and unexpected presence equally scared the shit out of us. On that same visit to Grayling, on our last morning at our rental cabin, I had another close encounter with a different eagle. I had walked down for one last, longing look at the Au Sable River, when I sensed I was being watched. I glanced up and over my shoulder — there, an eagle perched roughly 15 feet above my head. Thankfully, it didn’t pull the “offloading extra weight before flight” move (common for birds of prey) as it took off, or it would’ve been a long ride home to Grand Rapids.

I’ve been fortunate to get glimpses of eaglets – which look like fuzzy little Muppet alien gremlins – at a nest at Magee Marsh in Ohio and more recently at Grand Ravines Park in Ottawa County, Mich. At another popular birding destination, Sax-Zim Bog in northern Minnesota, I recall a snowy field filled with eagles – mostly bearing the brown heads of juveniles (always a good sign for the future!).

My favorite eagle moment came while golfing with my husband at The Rookery on Marco Island in Florida. Well, he golfs. I ride along in the cart and look for birds. Anyhow, we watched two eagles chase an osprey (another kickass bird of prey!) and harass it to the point where it dropped a fish onto the green about 20 feet from where we sat, slack-jawed. This was typical behavior – eagles regularly practice kleptoparasitism, a move in which one animal intentionally “steals” food from another animal – but it was incredible to witness up close.

So what’s next for eagles?

I’d like to believe I’ll forever have the option to take bald eagles for granted, and that future generations of birders will get to pretend to be too cool to care about seeing one.

I’m still uneasy, though, in spite of a currently stable population.

Avian flu is a growing concern. Lead poisoning remains a threat.

Human/eagle conflicts will increase as populations rise and habitats shrink.

Meanwhile, the current administration of the United States has its sights set on weakening policies, including the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, that protect birds like the bald eagle.

Some folks will say, “do you have to make everything political?!” But governmental policies guide and regulate corporate and private sector behavior. The impact on America’s public lands and wildlife is lasting and profound.

It is simply magical thinking to believe that birds and other wildlife won’t be harmed by opening massive tracts of federal lands to logging and mining while also defanging protections for migratory birds, water quality and air quality. History and science bear this out. We each must take accountability for our choices and actions. Those of us who care about birds must continue to speak up and advocate for the healthiest, most balanced and forward-thinking policies.

If scientists, conservationists and concerned citizens in the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s had sat idly by in the hopes that things would “work out on their own” we likely wouldn’t have bald eagles today outside of zoos or history books. Conservation doesn’t work with a “cross your fingers and hope for the best” or “set it and forget it” mentality. It requires consistent commitment, courage and a long memory.

Resources and references

https://www.nwf.org/Our-Work/Wildlife-Conservation/Success-Stories

https://www.audubon.org/news/will-bald-eagle-eat-your-outdoor-cat

https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/bald-eagle-fact-sheet.pdf

https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/news/ddt-still-killing-robins-50-years-after-first-warnings/

https://abcbirds.org/whats-good-for-insects-is-good-for-the-birds/

https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/stephen-moss/ten-birds-changed-world/

https://www.nrdc.org/stories/story-silent-spring

https://defenders.org/blog/2023/01/saving-bald-eagle-conservation-success-story

https://phys.org/news/2025-02-eagles-owls-dying-bird-flu.html

https://defenders.org/newsroom/trump-administration-rolls-back-protections-migratory-birds